George Washington’s Most Earnest Desire for the United States – to Command the Rivers at Fort Wayne

The Fighting Irish: Canal Builders and the Violence of Progress

December 17, 2021

Irishtown: Stories from an Emigrant Neighborhood

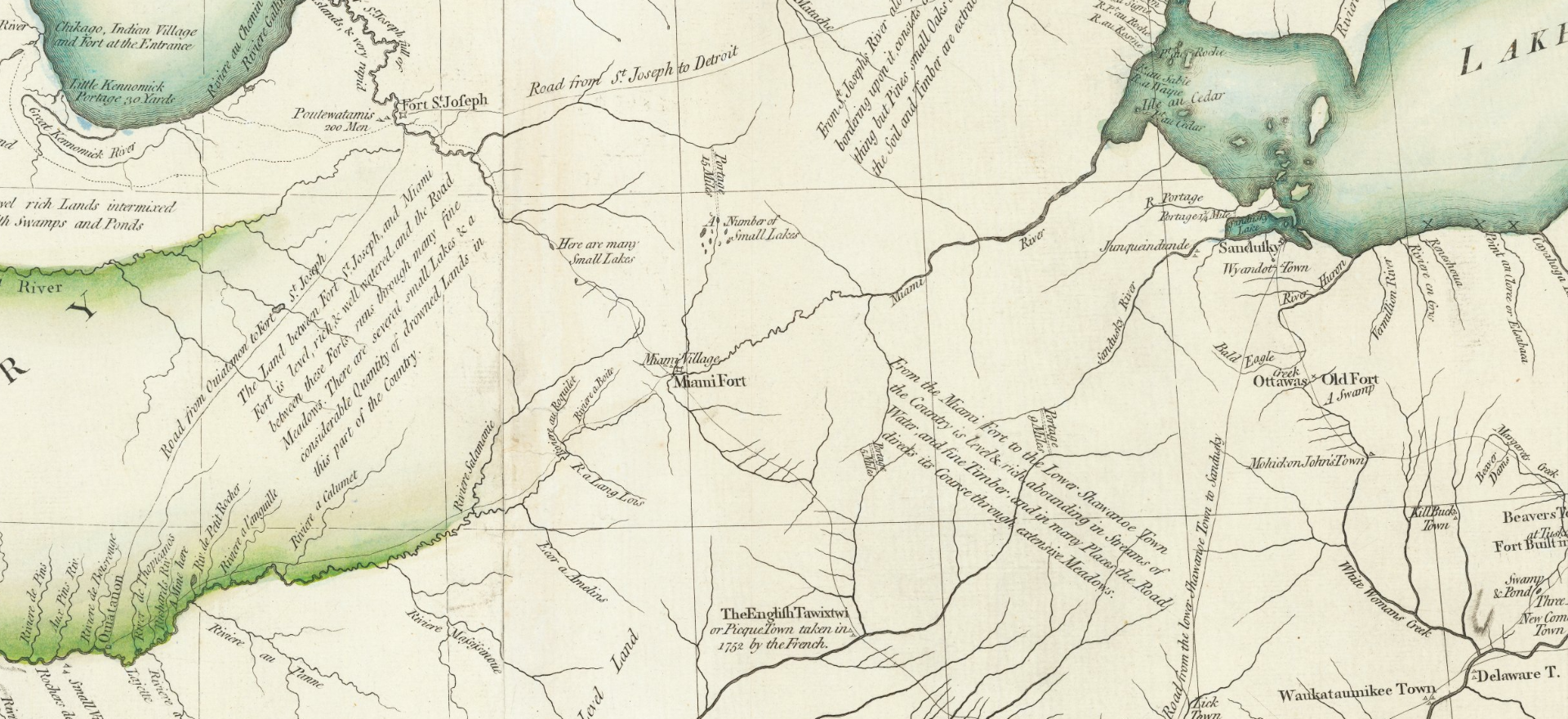

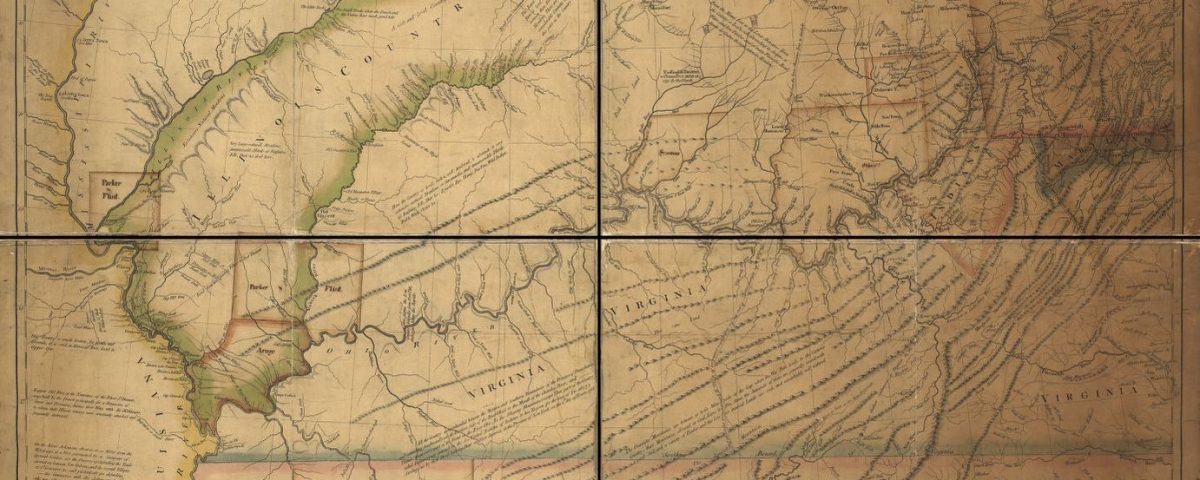

March 7, 2024In 1778, Cartographer Thomas Hutchins published a map that would become a personal favorite of our nations first President, George Washington. The work entitled “ A New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina” was an extraordinarily detailed and an important map used in the formation of the young nation. It’s lines and notes would be consulted by military commanders and political leaders for years to come – but perhaps most importantly, at the cessation of the Revolutionary War.

In combination with a 1755 map from John Mitchell, the Hutchins map was a primary resource for representatives of Great Britain and the United States, after the Revolutionary War, while negotiating the Treaty of Paris in 1783. It was used to designate areas of North America that the British would cede to the new United States. These lands were, according to the British, acquired by treaty with the many native tribes and were now given to the United States by treaty with the Treaty of Paris.

Washington would have been already well-familiar with the Hutchins map and recognized that the confluence of the Maumee River, St Joseph River and St Marys River held strategic value for the United States.

On the study of the Hutchins map, and other maps of that period, Washington wrote to his French friend Jean Francois comte de Chastellux in October 1783, “Prompted by these actual observations, I could not help taking a more contemplative and extensive view of the vast inland navigation of these United States, from maps and the information of others; and could not but be struck with the immense diffusion and importance of it.”

The Hutchins map makes note of the Miami Villages (Kekionga) at the headwaters of the Maumee River which formed the eastern terminus of a portage between the Maumee and the Little Wabash to the West. By portaging a canoe or other small watercraft just a few miles overland, the traveler could put his boat back in the waters of the Wabash River, and from there to the Ohio, the Mississippi and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. These rivers formed an important network of highways that would allow the United States to exert control and influence along the western boundaries of the nation.

The Hutchins map also contains a note that “The Land between fort St. Joseph (Niles, Michigan) and Miami Fort (Fort Wayne, Indiana) is level, rich, & well watered and the Road between the Forts runs through many fine meadows. There are several small Lakes & a considerable Quantity of drowned Lands in this part of the country” Another note mentions “Here are many small lakes” – to George Washington, with the trained eye of a surveyor, this would be ideal country for future settlement.

In his letter to Jean Francois comte de Chastellux, Washington wrote, “Would to God we may have the wisdom enough to improve them. I shall not rest contented ‘till I have explored the western country, and traversed those lines … which have given bounds to a new empire.”

As to the native Americans who inhabited those lands, Washington intended to be fair (in his estimation) but ultimately he informed Congress that they (native Americans) had chosen to side with our enemies during the American Revolution and so should ultimately be compelled to retire from the land east of the Mississippi just as their Allies the British had been in the Treaty of Paris.

“The Indians should be reminded that despite all the advice and admonition which could be given them at the commencement; and during the prosecution of the war” they “were determined to join their arms to those of Great Britain and to share their fortune’ so consequently, with a less generous people than Americans they would be made to share the same fate, and be compelled to retire along with them beyond the Lakes.”

George Washington Letter to Congress, The Papers of George Washington

Instead of demanding the lands immediately, Washington favored a more measured approach in which the United States would negotiate new treaties and purchase the lands from native tribes as the pace of expansion required them.

In the years after the Treaty of Paris, Washington’s plan of peaceful negotiations with the native tribes proved elusive and the United States had trouble containing it’s citizens within its boundaries. Between 1784 and 1789 some 1500 settlers were killed along the Ohio River – many of those attacks being carried about by the Miami and Shawnee who inhabited the villages of Kekionga. With all of this in mind, and with British provocations increasing in the Northwest, Washington would eventually set his sights on Kekionga.

In 1789, Washington inquired through Northwest territory Governor St. Clair if the Indians living along the Wabash would be “inclined for peace” and St. Clair’s response indicated they preferred war.

By taking Kekionga and establishing a Fort at present day Fort Wayne, Washington could check British advances from Canada, control the important portage and river traffic at the Headwaters of the Maumee and restrain the Miami and Shawnee from acting violently towards American settlers.

In early 1790 peaceful overtures were rebuffed by the native tribes leading Washington and his Secretary of War, Henry Knox , to decide for war. Josiah Harmar was selected to command the expedition and ordered to destroy Kekionga and establish a United States installation at the headwaters of the Maumee.

And thus the war for the Old Northwest began – with three separate United States armies attacking the Confederated tribes of native Americans over the course of five years. Harmar’s Army of 1790 would be defeated at the ruins of Kekionga in 1790. The Northwest territory Governor, Arthur St Clair would replace him and sustained the worst loss in American history at Fort Recovery, Ohio in 1791.

A third army under General Anthony Wayne, defeated the Confederation at Fallen Timbers in 1794. Immediately after his victory, Wayne came straight to the headwaters of the Maumee and built his fort at Fort Wayne. This finally drove the native confederation to the treaty table at Greenville in 1795.

While George Washington would not live to see his vision for the Northwest complete – Andrew Jackson would. Little by little, lands were taken by treaty until the Indian Removal Act of 1830 demanded the tribes of Indiana to be moved west of the Mississippi.

On October 11, 1846 the forced removal of the Miami was put into motion and natives who were rounded up were forced onto canal boats at Peru, Indiana and taken westward to their temporary homes in Kansas.

– Paul Calloway

Fort Wayne, Indiana

2 Comments

Do these maps still exist and if so, where are they held?

Thank you.

Yes they are! These maps are held at the Libarary of Congress – in their MAPS division. Images are available online at the following link.

https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71002165