The Fighting Irish: Canal Builders and the Violence of Progress

Congress Investigates Josiah Harmar for his Defeat at Kekionga (Fort Wayne)

December 15, 2021

George Washington’s Most Earnest Desire for the United States – to Command the Rivers at Fort Wayne

February 21, 2022The Irish emigrants in 19th century America were exploited by the emerging industrial machine that promised to provide infrastructure and unite the citizens. Considered by many to be the lowest class, the refuse of the world, they would defy the odds and build a network of canals that would change the way passengers and goods were transported from the East Coast to the Midwest. Along the way, they suffered for their new country, yet they rose above their struggle to a position of prominence and would be celebrated in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Irish had been in America since its humble beginning, however, during the 19th century, a mass exodus would begin. Fleeing their protestant English landlords and the oppression of British rule, many Irish emigrants sought the promise of freedom that America had to offer. A living wage and the right to practice their Catholic religion without discrimination was what they wanted, a small slice of the American dream. So, they sold what they had and spent most of their savings too on passage to the promised land.

Struggles of the Irish Emigrant. The passage to America was not easy. They traveled on converted cargo ships, some of which had been used by slave traders, and unlike the cruise ships of today, they were treated more like cargo than passengers, spending the voyage in the cargo hold with little food or fresh water and the constant threat of disease was rampant throughout the dark quarters covered in vomit, urine, and feces. Many would not survive the 3,000-mile voyage, those who did set foot on the shores of their new home were poor, sick, and hungry as they searched for shelter and work in crowded cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Boston.

In the 1830s, Irish emigrants more often traveled alone or with siblings rather than with nuclear families as they had in the past. Among those landing in New York, about two-thirds were male, and in their early twenties (Miller 199). Unlike Irish emigrants who had arrived in earlier years, many of these emigrants were unskilled laborers, who brought with them only their hands as capital and were “without acquired skill of any kind” (198).

The citizens of those cities were none too happy about the destitute and unskilled Irish living among them. And on top of that, they did not like the fact that they were Catholics too. Many of the sick and destitute ended up in almshouses (also known as poorhouses) and this was seen as proof by many that the Irish were a burden on the taxpayers. By the 19th century, almshouses were home to not only the poor but the mentally ill and alcoholics too. It was a last resort for the poor and by no means the desired destination. One of the most infamous, Tewksbury Almshouse in Massachusetts, was a place worthy of an Edgar Allan Poe short story. One account states that a corpse was sold to students at a dental school for $14. The corpse, that of a grown woman, had come from Tewksbury. Other accounts were even more barbaric, a tanner is said to have in his possession the tanned skin of an African American. It had been sold to him by a man from Harvard, who had received it from Tewksbury. Reports of the cruelty and unspeakable things that happened there would only come to light in the late 19th century and the horrors perpetrated there are still being talked about today (Tewksbury).

The options were limited for the Irish emigrant. Newspapers of the day printed ads seeking housemaids, or laborers with the caveat “No Irish need apply. Despite their situation, the Irish emigrants were hopeful, being despised by their new countrymen paled in comparison to what they endured back home in Ireland, they just needed to find their way.

Westward Expansion.

Let us bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals. Let us conquer space.

John C. Calhoun, 1817

The words of John C. Calhoun inspire thoughts of a time when America was still a raw and open landscape yet to be conquered. Though the cities of the eastern seaboard had been there for some time, travel westward was still a difficult undertaking. Pathways through the wilderness were primitive by today’s standards. Some of them were nothing more than old Indian trails that had been used for thousands of years before the arrival of European settlers. Travel by river was limited to regions that had navigable rivers and a solution was needed to bridge the gap between larger urban centers like New York City and the frontier. Calhoun, known for his pro-slavery rhetoric, in a speech from 1837 would state “I hold then, that there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other” (Calhoun 6). He was referring to African American slaves at the time, but his words could have easily been directed at the Irish emigrant too. With the Erie Canal already completed, an extension was being planned that linked the Great Lakes with the Indiana frontier. It would be called the Wabash-Erie Canal, and as was the case with the Erie Canal, it would be built, primarily by Irish emigrants, who were called “navvies” (Castaldi 2002).

In January 1832, the village of Fort Wayne, with a population of three hundred, celebrated the official approval for construction to begin on the Wabash and Erie Canal. The previous year the state legislature had authorized a loan of $200,000 due to the campaigning of the Honorable Judge Samuel Hanna, a Fort Wayne resident of Irish descent who is considered by many to be the founder of the city of Fort Wayne. Judge Hanna was in the position to heavily influence the construction of the canal, being the canal commissioner, fund commissioner, and chairman of the canal committee (Griswold 303).

The citizens of Fort Wayne had cause for celebration. A meeting was held at the Masonic Hall with Henry Rudisill presiding and the Irishman David Colerick as secretary. It was decided that on February 22, George Washington’s birthday, work on the canal would begin and a great celebration would be held to mark the occasion (Griswold 305).

On the day of the First Canal Celebration, the citizens gathered at the courthouse square and marched in unison to the site where the work on the canal would begin. The procession was led by two musicians and the members of the canal commission as well as a flag-bearer carrying the American Flag. The officials were followed by citizens and guests. Upon arrival, the congregation was addressed by Charles Ewing followed by canal commissioner Jordan Vigus. With the words “I am now about to commence the Wabash and Erie canal, in the name and by the authority of the state of Indiana.”, Judge Hanna and other officials sunk their shovels in the ground and broke ground on the Wabash & Erie Canal (Griswold 306).

The Wabash & Erie Canal. The construction of the canal brought hundreds of workers to Fort Wayne, the majority of which were Irish emigrants (Griswold 307). The daily life of a canal worker was a hard one. They slept in horrible conditions, the food was not great, and they worked long hours from dawn till dusk. On top of their living conditions, they worked in some of the most inhospitable conditions. Through humid and mosquito-infested swampland and across snow-covered prairies, they drained the swamps and thrust their picks into the frozen tundra of midwestern winters (Dearinger 14).

If the harsh working and living conditions were not bad enough, the policies they were subjected to by both the companies they worked for and the state they were working in made their lives a living hell. They had deadlines to meet and there was no Occupational Health and Safety Administration OSHA to protect them. Even the communities despised the raucous canal workers that were dirty, oftentimes illiterate, and sometimes prone to drunkenness after they clocked out for the day (Dearinger 14).

Allen County would be the entry point for the canal, in Indiana. It would link up with the Miami-Erie Canal in a stretch known as the Junction State Line Section, however, the connection would not be finished until 1843 after the urging of Indiana to the Ohio State House to finish it. This would link up Fort Wayne with Toledo, Ohio. From Fort Wayne, the canal proceeded west into Huntington County, passing briefly through the southwest edge of Whitley County (Castaldi 2002).

On the western edge of downtown Fort Wayne, an aqueduct was constructed so that the canal could cross the Saint Marys River. Aqueducts have been historically linked to the Romans; however, the technology can be traced to much earlier civilizations like the Greeks and Assyrians as early as the 7th century BCE. An aqueduct can be constructed of stone, brick, or even wood and is used to carry water over a distance and has been used to carry water over rivers as well as changes in elevation.

A few miles east of Huntington, in what is now the town of Roanoke, Dicky Lock No. 4 was built. This was the first lock from the Summit Level west of Fort Wayne. A lock, like an aqueduct, was a feat of engineering. It enabled vessels to travel through areas where stretches of water are at different levels. The chamber is enclosed by a Lower and Upper gate. The water level could be changed to accommodate the incoming vessel by the raising and lowering of these gates. This process allowed a canal boat to travel up and over a mountain, for example, and back down the other side, through a series of locks. The remnants of a canal culvert are still visible today near a modern-day tavern named “Lock No. 4” in its honor (Castaldi 2002).

As the canal workers moved west from Fort Wayne, they entered more rural and sometimes sparsely inhabited areas. And when they crossed through Huntington County into Wabash County, tempers would come to a head near what is modern-day Lagro.

The Irish War. By 1835, the canal had reached the town of Lagro in Wabash County, Indiana. The backbreaking work and wretched living conditions fueled a fire of discontent among the workers. The Fardowners from “farther down” in Ireland had been at the mercy of the Corkonians from Cork due to the sheer numbers of Corks. And some of the grievances were rather petty, seen through the spyglass of history. The Corkonians, it seems, enjoyed six shots of whiskey in addition to their daily pay while the Downers only received four. As you can imagine this was a point of contention and there was resentment (Castaldi 2004). By the time the construction reached Wabash County, the Fardowners began to outnumber the Corkonians and they were bent on revenge. Nightly assaults, arson, and even an occasional murder perpetrated by locals who despised the Irish canal workers or by rival factions of the Irish workers themselves contributed to a powder keg of unrest and it would explode in an event that came to be known as “The Irish War” (Dearinger 22).

On July 10, 1835, armed and angry workers from both factions were prepared to meet in battle, to settle their differences. Fortunately, canal leaders and local militia were able to stop the skirmish before it even began. As one historian put it “The Irish war ended as wars should end, by not starting” (Wimberly 69). However, in other locales across the Midwest of the United States and Canada, the violence of progress was not so easily quelled.

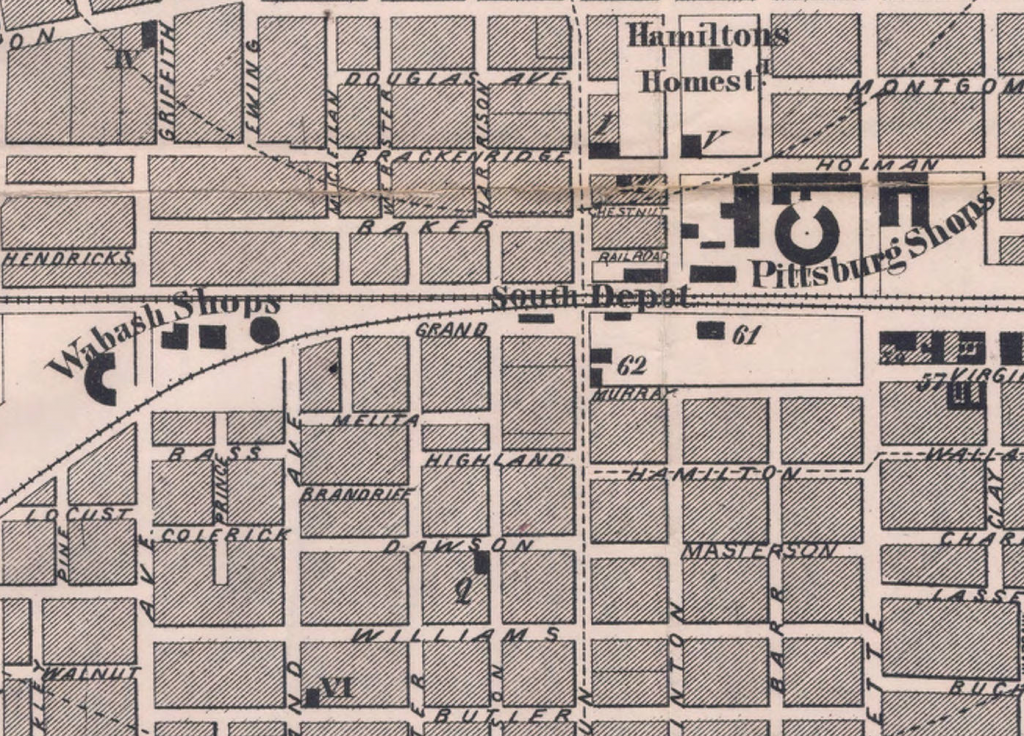

Settling Down in Irish Town. After completion of the Wabash and Erie Canal, many of the Irish workers chose to stay in Indiana. Some of them chose Fort Wayne to lay down roots, due to employment opportunities with the railroad and other industries based in the city. By the mid-19th century, a neighborhood was established south of downtown between Calhoun and Fairfield. This neighborhood came to be known as “Irish Town” because of the predominantly Irish residents that called it home.

It was what we might call a blue-collar neighborhood today. Many of the residents worked for the railroad or in one of the factories or mills near downtown. Most of the homes were boarding houses, with multiple tenants living under one roof. Many of the businesses in Irish Town were owned not only by Irish but German emigrants too, and many of them lived in residences above their place of business.

It was a huge step up from living on the streets of New York City, in the almshouses, or even in the shanty camps of the canal workers. The railroad depots and the factories and mills were all within easy walking distance of the neighborhood. Though not an extravagant lifestyle by any stretch, for these Irish who had endured so much, it was a life that they could have only imagined only a few years before. Welcomed by early Irish pioneers to the region like Samuel Hanna and Allen Hamilton, who had prospered in business and made a name for themselves, the Irish found a home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and most of all acceptance.

Living History. The monstrous undertaking that was the construction of the Wabash and Erie Canal would appear to be a failure to some. It would only be used for a short time in Indiana. The railroad proved to be a more economical and efficient form of transportation for people and goods. The canal was abandoned in most places.

Remnants of the canal can still be found in places like Fort Wayne, Roanoke, Lagro, and Delphi, where they have created a remarkable tribute to the canal workers. A replica shanty camp with log cabins, shacks really, can be booked for overnight stays and a replica of a 19th-century canal boat travels one of the remaining stretches of the canal, providing visitors with a living history experience. Gone is the towpath and mule with its driver, replaced by the internal combustion engine.

Unlike the xenophobia they had experienced on the east coast, Indiana embraced its Irish people and their religion too. As it turned out, the wherewithal it took to build the canal looked great on a resume, so to speak, as employers hired the Irish for their strong work ethic. During the construction of the canal, The University of Notre Dame du Lac, a Catholic university, would be founded in South Bend. It would later be known simply as Notre Dame, and its mascot, the Fighting Irish.

Irish Town Today. If no one told you there was a neighborhood in Fort Wayne once known as Irish Town, you probably would never know it existed. There are no signs or monuments to mark its contribution to the building of the city. You will however find one big reminder of the neighborhood’s Irish past though, St. Patrick’s Church, completed in 1890.

St. Patrick’s Parish was created in 1889, with Father Thomas O’Leary appointed as its first pastor. He immediately began to plan for the erection of a church and acquired five lots for it to be built on. Sadly, Father O’Leary would not live to see the completion of the church, he died of acute appendicitis only three weeks after being appointed. Father Joseph F. Delaney would succeed him, and the construction would be completed the following year.

At the corner of Dewald and Harrison, just outside the church, a figure stands like a sentinel, beckoning weary travelers to come in, it is a statue of the Apostle of Ireland himself, Saint Pádraig with his outstretched hand holding a shamrock as if to remind future generations that they are passing through Irish Town.

The culture of the Irish still resonates throughout the downtown area too. Irish food and drink can be found at JK O’Donnell’s Irish Pub and O’Reilly’s Sports Bar. You would be hard-pressed to find a pub in Fort Wayne that does not offer a pint of Guinness or a shot of Jameson to its patrons. And on March 17th of every year, the St. Marys River turns green, as Irish descendants invite everyone to be Irish, even if only for a day.

The most famous Irishmen of the city’s history left their mark too. If you see places or streets with names like Hanna or Hamilton, you are seeing the legacy of two of Fort Wayne’s founders. And, we cannot forget General Anthony Wayne, son of an Irish emigrant, whose name can be found all over the city, and whose surname is our namesake.

Conclusion. Beyond Fort Wayne, the Irish would prosper too. Irish neighborhoods in metropolitan cities across the United States can be found. Where a strong work ethic is still something men and women of Irish descent take pride in. I wonder sometimes, how many of them know how tough the Irish who came before them had it. I think most of us consider being Irish a badge of honor in modern-day America, but it was not always that way, and it was not that long ago that the Irish were despised. Lest we forget.

A little over a century after the completion of the canal, an Irish American named John Fitzgerald Kennedy would show how far the Irish had come in America when, on January 20, 1961, he was inaugurated as the first President of the United States that was both a Catholic and of Irish descent. President Kennedy would deliver an inspiring inaugural address that day, which is still quoted today (Kennedy). He would conclude with the following words that I think are an appropriate conclusion to this paper:

Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own.

President John F. Kennedy, January 20, 1961 – Inaugral Address

Works Cited

Castaldi, Thomas E. Wabash & Erie Canal Notebook I: Allen and Huntington counties. T. Castaldi, 2002. Print.

Castaldi, Thomas E. Wabash & Erie Canal Notebook III: Wabash and Miami counties. T. Castaldi, 2004. Print.

Calhoun, J. C. (John Caldwell)., The United States. Congress 1836-1837). Senate. (1837). Speeches of Mr. Calhoun of S. Carolina, on the bill for the admission of Michigan: delivered in the Senate of the United States, January 1837. Washington, D.C.: Duff Green. Print.

Dearinger, Ryan. The Filth of Progress. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019. Print.

Griswold, B. J. (Bert Joseph), and Samuel R. Taylor. The Pictorial History of Fort Wayne, Indiana: A Review of Two Centuries of Occupation of the Region About the Head of the Maumee River. Evansville, Ind: Unigraphics, 1971. Print.

Kennedy, John F. “John F. Kennedy Inaugural Address.” The American Presidency Project, University of California Santa Barbara, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/234470. Transcript. Web

McMahon, Eileen M. “Canal Diggers, Church Builders: Dispelling Stereotypes of the Irish on the Illinois & Michigan Canal Corridor.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998) 111.4 (2018): 43–81. Web.

Madison, James H. Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014. Print.

Miller, Kerby A. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America. Oxford University Press, 1988. Print

Perry, Jay M. 2009. Shillelaghs, Shovels, And Secrets: Irish emigrant Secret Societies and The Building of Indiana Internal Improvements, 1835-1837 [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University Graduate School, Department of History, Indiana University. Web

Tewksbury Almshouse investigation. (1883, April 24). The Lowell Weekly Sun. Retrieved [December 1, 2021]] from /?p=10399. Web

Wimberly, W. W. Hanna’s town: A little world we have lost. Indiana Historical Society Press, 2010. Web.